The great advantage of living in today’s world is being able to tell your story to the world and in the same way, being able to read the stories from around the world and find that there is something about humans that seems to be a common thread in all cultures and all civilizations – a spirit to survive.

Our reading list here at Team Thinkerviews always has a book or two representing authors from around the world whose work has become iconic representation of their times and we had a book named widl Swans : Three Daughters of China by author Jung Chang on our list for 2021, as we shared with you at the start of this year :-).

| Book Title | : | Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China |

| Author | : | Jung Chang |

| Publisher | : | William Collins(27 Oct 2011) |

| # of Pages | : |

720 (Paperback) 6465 KB; 721 (Kindle EBook) |

| # of Chapters | : | – |

| Purchase Link(s) | : |

|

First published in 1991, this book tells the story of three generations of women – spanning through a big part of 20th century, and has been widely loved by international audiences selling millions of copies world wide. I enjoyed reading this book and here are my thoughts on it for you on behalf of Team ThinkerViews.

This Is Here In For You

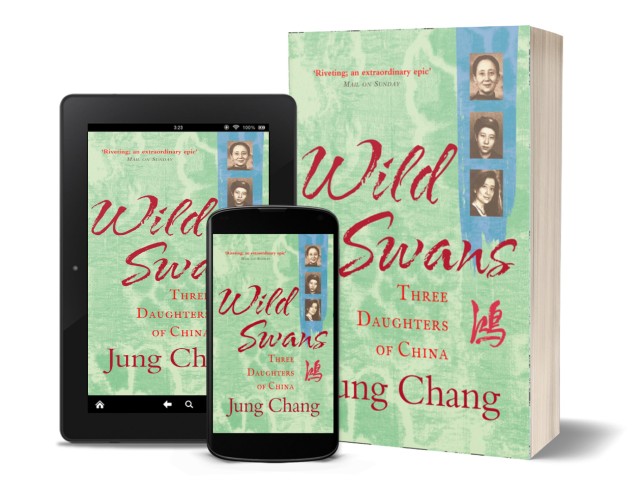

Coverpage:

Let us take a look at the cover page of this book.

Wild Swans – Three Daughters of China by Jung Chang | Book Review

I read the 21st anniversary edition of the book, published by Harper Press, with a cover page done in soothing marine blue-grey shades showing the name of the book and the author in orange. The Chinese representation of wild swans in done in red – probably symobilising the red rule. The most interesting part is the side strip showing photographs of three women – three generations – author Jung Chang in the bottom most image, her mother in the middle and her grandmother at the top.

The book cover gives you a feel for the story that is within and also an indication that it is not a work of fiction.

An interesting cover page…

Storyline:

Starting in 1909, Jung Chang starts to tell us about her grandmother Yu-fang who became the concubine of a warlord general at a tender age of fifteen in year 1924. This was China still under the rule of warlords. Yu-fang’s family lived in provincial town of Yixian in southwest Manchuria, abour a hundred miles north of the Great Wall and about 250 miles northeast of Peking. Her father was a police official here and saw it as the best way to his progress if his beautiful daughter could be tied to a powerful General Xue Zhi-heng.

The alliance was made and the General set up his new concubine in a big house in Yixian and travelled away. Six years later, he returned and they conceived a daughter Bao Quin/De-hong. When the General died, Yu-fang fled his house in night worried about safety of her daughter.

After a few years of living in fear that she may yet lose her daughter, Yu-fang met Dr Xia and became his second wife. Dr Xia was also much older than her and already had a big family from 1st marriage who was not in favour of this new marriage. Family dispute led them to leave the town of Yixian and make a new life in city of Jinzhou in 1936. This is where De-hong grew up and joined communist revolution at early age just as world war II was ending and the Japanese and Russian influences were withdrawing to make way for changes within China.

De-hong’s life was much different from her mother with her education, her political convictions and at young age she left home. She met Shou-yu – an officer in the communist army and they were married. De-hong’s life wasn’t easy though. As part of the new regime, they went through physical ordeals and challenges while working for the communist cause. She suffered ill health and miscarriage, misunderstandings with her husband, poor living conditions all through the fifties, while she brought five more children int he world – Er-hong/Jung being her second daughter of them.

As Jung grew up, she saw her parent’s lives closely. Her grandmother was also living with them and caring for children when she could. Like her generation, Jung was also part of the cultural revolution era and tells us in detail about the life of her family through the fifties to the seventies. She had to watch painfully as the system turned around on her parents who had been loyal communists, so much so that her father was prosecuted, became mentally ill and eventually died facing the brutalities of the rulers that he had once whole-heartedly believed in.

Jung herself had to spend time away from family, work as a peasant, an electrician, until she could manage to get a place at a university. After years of struggle, she finally managed to get a scholarship to England for further study of linguistics. As she left the country in 1978, she wondered about both past and the future of herself as well as china.

Views and Reviews:

As you can see, the book spans almost over a century, as Jung Chang tells us about the lives of great grand parents at the start of twentieth century, how most families wouldn’t even bother to name a girl, but would call them number one girl, or number two girl – her great grandmother being one of them. A nameless girl, raised by an uncle and betrothed at age of six to the future baby of a family friends. Her life was representative of millions of people of her times, and all throughout her life she looked after the family and yet was considered dependent upon the male family members.

Her daughter Yu-fang was beautiful and was named upon her birth in 1909. Her feet were broken at age of two. This was the custom prevailing for centuries to ensure women had tiny feet throughout their lives, as they were considered beautiful. The resulting ugliness and agony that they endured throughout their lives was of little concern. Its surprising how many such customs had evolved around the world, whether it is piercing, or elongated necks, or tiny, bound feet. Being beautiful also meant that her father could use her for his official promotions. To have no say in your future was also not so uncommon in those days, and in a lot more places than just China.

And so by the 1940s, when you compare the life of De-hong and her freedom to pursue communist cause, you can see how drastically lives of ordinary women had changed in a span of 40 years. But as they were given freedom, they were also expected to almost give up their femininity. They had to show physical strength, endurance, never complain and suffer in a different way for a cause that took over their lives completely.

But the world is a cruel place. And usually it is the much loved cause that tends to turn around and become a cause of misery. It is very painful to read the story of Jung’s father who almost neglected his family at times for his work and to see him go literally mad with the grief when it all morphs into unforeseen cultural revolution, eventually to die in disgrace. Although Jung’s tireless mother got him absolved after many years of his death, it is hard to see so much waste. And he was only one of them.

As the author says, there were millions of people and millions of families, who would have similar stories to tell. You can see why this personal story almost also becomes a social history story as you see how the country around them changes and how they adapt to changes in their circumstances. It is hard not to admire their courage, their spirit and their resilience as they continually fight for survival and a better life.

I also liked many instances in this book where the author talks about the ancient civilization of China and how radical some of the effects of 20th century events were:

Wherever we went as we travelled down the Yangtze we saw the aftermath of the Cultural revolution: temples smashed, statues toppled, and old towns wrecked. Little evidence remained of China’s ancient civilization. But the loss went even deeper than this. Not only had China destroyed most of its beautiful things, it had lost its appreciation of them, and was unable to make new ones.

This is something we need to remember even today, as we blindly follow the trend of condemning our own cultural values as ‘orthodox’ and moving into the new self-centered world. The author also talks about the traditional Chinese obsession about other races being ‘barbarians’ and the following snippet actually is so like our own ‘kue-ka-medhak’ simili:

We were like the frogs at the bottom of the well in the Chinese legend, who claimed that the sky was only as big as the round opening at the top of their well.

As the story covers the political journey of China in so much detail, the author also remarks on how the rulers/ politicians are apt to take advantage of human weaknesses:

The core of this philosophy seemed to be that human struggles were the motivating force of history and that in order to make history ‘class enemies’ had to be continuously created en masse. I wondered whether there were any other philosophers whose theories had led to the suffering and death of so many.

He ruled by getting people to hate each other. In bringing out and nourishing the worst in the people, he had created a moral wasteland and a land of hatred.

The book has a huge canvas geographically as well as socially and is filled with many quotes and observations I would like to share, but the one below summarizes the message of hope above all:

I had experienced privilege as well as denunciation, courage as well as fear, seen kindness and loyalty as well as depths of human ugliness. Amid suffering, ruin and death, I had above all known love and the indestructible human capacity to survive and to pursue happiness.

I enjoyed reading the book and it was a learning experience in understanding the lives of people living in China of twentieth century. There is so much cultural complexity in such a big and densely populated nation that unless you grow up in it, you can only scratch the surface. The book contains maps, references and some old photographs to make it more relatable and there are also some notes by the author explaining how pronunciation of Chinese words works. I also tried this in audiobook format, and the listening experience was very useful in terms of understanding some of the Chinese words and expressions.

Summary:

A book worth reading, if you are looking at spending a few days following lives of a few generations and see the country around them through their eyes, as it changed through twentieth century.

ThinkerViews Rating:

Around 7.5 out of 10.

Quick Purchase Link(s):

- Buy – Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China By Jung Chang – Paperback – Amazon India

- Buy – Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China By Jung Chang – Kindle Ebook – Amazon India

- Buy – The Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China By Jung Chang – Paperback – Amazon US

- Buy – Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China By Jung Chang – Kindle Ebook – Amazon US

Over To You:

If you already have read the book do share your remarks and thoughts via comments below. Does this review help you in making your decision to buy or read the book? Do not forget to share this article with your friends over various social networks via Twitter, Facebook and others. And yes, you may like to subscribe to our RSS feeds and follow us on various Social networks to get latest updates for the site to land right in your mail box.

ThinkerViews – Views And Reviews Personal views and reviews for books, magazines, tv serials, movies, websites, technical stuff and more.

ThinkerViews – Views And Reviews Personal views and reviews for books, magazines, tv serials, movies, websites, technical stuff and more.